法国兴业银行(Société Générale)直言不讳的全球策略师阿尔伯特·爱德华兹(Albert Edwards)——他甚至自称“永久熊市论者”——确信,当前主要由高估值科技股和人工智能股驱动的美国股市正深陷危险的泡沫之中。(需要明确的是,法国兴业银行并不认为美股或AI股存在泡沫,并指出爱德华兹的职责是提供内部不同观点。)尽管历史常常重演,但爱德华兹近期警告称,本轮周期崩盘的环境已发生根本性变化,可能导致经济和平民投资者遭受更深远、更痛苦的清算。

“我认为存在泡沫,不过话说回来,我总是认为有泡沫,”爱德华兹最近在彭博社的梅琳·萨默塞特·韦布(Merryn Somerset Webb)的播客节目《Merryn Talks Money》中表示,并指出每个周期总有一个“看似非常合理、极具说服力的叙事”。然而,他的结论坚定不移:“最终会以悲剧收场,这一点我非常肯定。”

爱德华兹在接受《财富》杂志(Fortune)采访时表示,此前关于泡沫的理论“在1999年和2000年初非常令人信服,在2006—2007年也是如此”。他说,每次“市场上涨都如此迅猛”,以至于他不再谈论泡沫,“因为客户会对你重复同样的话却总是说错感到厌烦”,直到泡沫破裂后他们才会改变态度。“通常,当人们被泡沫冲昏头脑时,他们根本不想听,因为他们正在赚大钱。”

正如他本人常指出的那样,爱德华兹以极度看空的市场策略师闻名,他做出过一些引人注目且夸张的预测,经常对股市大幅崩盘和经济衰退发出警告。他的过往记录包括著名的准确预测互联网泡沫,但也包含一些未应验的警告,例如预测标普500指数可能从峰值下跌75%——比2008年金融危机的低点更糟。当《纽约时报》在2010年报道爱德华兹时,他们指出,这位面带微笑、穿着勃肯鞋的分析师自1997年以来就一直预测美国股市将出现日本式的停滞(他在接受《财富》杂志采访时重复了这一预测)。

尽管如此,爱德华兹仍坚持认为,当前情况与1990年代末的纳斯达克泡沫有明显的相似之处:科技股估值极高,一些美国公司的远期市盈率超过30倍,而这都由引人注目的增长叙事所支撑。爱德华兹认为,正如上世纪90年代科技、媒体和电信(TMT)行业吸引了大量(有时是浪费的)资本投资一样,今天的狂热与那个早期时代如出一辙。不过,有两个关键差异可能导致这次的结果要糟糕得多。

缺失的催化剂与融涨风险

爱德华兹解释说,在以前的周期中,泡沫破灭的催化剂通常是货币当局的紧缩周期——即美联储加息,从而暴露市场泡沫。这一次,随着美联储降息,这一催化剂明显缺失。美国银行研究部指出,央行在通胀上升时降息的情况十分罕见,自1973年以来仅占16%。不祥的是,美银在八月份发布了一份关于“2007年幽灵”的报告。

爱德华兹预测,美联储不会收紧政策,反而会因为美国回购市场的问题——这是大衰退时期的另一个幽灵——而停止量化紧缩,并可能“很快”转向量化宽松。美联储本身在2021年就回购问题发布了一份工作人员报告,报告中写道2007年至2009年间的交易“凸显了美国回购市场的重要脆弱性”。回购问题在疫情期间再次出现,里士满联储指出利率从2019年开始“急剧飙升”。

爱德华兹告诉彭博社,缺乏鹰派政策可能导致“进一步融涨”,使得最终的破灭更具破坏性。爱德华兹自嘲道:“我只是厌倦了看空,基本上就像摇着锁链说‘这都是泡沫,全都要崩溃’。”他说,他明白这个泡沫实际上可能持续的时间远超像他这样的永久熊市论者认为合理的时间,“而实际上,正是在那时,会突然冒出一些意外事件,抽走泡沫的根基。”

“人工智能泡沫更令人担忧的是,”爱德华兹告诉《财富》杂志,“经济对这一主题的依赖程度有多深,不仅仅是推动增长的企业投资,”还有消费增长由顶层五分之一人口主导的程度远超平常。换句话说,那些重仓股票的美国最富有人群,对经济的推动作用比以往任何泡沫时期都大,占消费的比例也大得多。“所以,如果你愿意这么说,经济比'87年股灾时更脆弱,”爱德华兹解释道,股市25%或更大幅度的回调意味着消费支出必将受到影响——更不用说50%的暴跌了。

爱德华兹告诉彭博社,他担心被卷入市场、被鼓励“逢低买入”的散户投资者广泛参与。爱德华兹警告说,“股市永远不会下跌”这种信念是危险的,并认为下跌30%甚至50%是完全有可能的。美国社会的不平等以及财富被“股市吹胀”的高收入人群财富高度集中是爱德华兹主要担忧的问题,他指出,如果股市出现重大回调,那么美国的消费将“受到非常、非常严重的打击”,整个经济都将受损。华尔街那些不那么极端看空的人士,如摩根士丹利财富管理的丽莎·沙莱特(Lisa Shalett),也日益认同这一观点。

爱德华兹告诉《财富》杂志,从很多方面看,市场早该回调了,他指出除了疫情期间的两个月,自2008年以来就没有出现过衰退。“这时间真他妈长,而商业周期最终总是会进入衰退的。”他说时间太长了,以至于他作为永久熊市论者的本能都感到困惑。“事实上我现在对即将发生的崩盘不那么担心了,这反而让我担心,”爱德华兹笑着补充道。

爱德华兹告诉《财富》杂志,他经历过各种周期和泡沫,并在1990年代中期确立了他永久熊市论者的地位,当时他感觉到遥远的亚洲正在发生一场地震。“你在这个圈子里混了几次,就会变得愤世嫉俗,”他说,然后又纠正自己:“这个词不对。你会变得对完整的叙事极度怀疑。”他自豪地重复讲述他在90年代在德利佳华(Dresdner Kleinwort)工作时,如何以怀疑的态度撰文评论当时马来西亚的经济繁荣,结果却惊讶地发现泰国先爆发了危机。尽管如此,他说,“因为我的文章,我们失去了(在马来西亚的)所有银行牌照,”并补充说,这个故事仍然自豪地钉在他的X.com账号上。

“我基本上算是得躲在桌子底下,”爱德华兹谈到他内心的熊市观点在公司内部得到的反应时说道。“企业金融银行部门当然不乐意失去所有银行牌照。但回过头看,你知道,他们避免了在马来西亚危机爆发前最后一年向其放贷。他们事后也没谢我。”

财政失控与蟑螂

除[股权估值外,爱德华兹一直强调另外两个指向系统性脆弱性的主要潜在风险。首先,爱德华兹强调了西方由“财政失控”驱动的长期通胀风险。尽管中国带来短期的周期性通缩压力——其GDP平减指数已连续12个季度同比下降——爱德华兹表示,他相信对于负债累累的西方政客来说,阻力最小的路径将是“印钞”。在某个时间点,财政可持续性的计算“根本对不上”,迫使央行通过“收益率曲线控制”或量化宽松进行干预以压低债券收益率。

这就引出了爱德华兹长期持有的关于日本的观点,他称之为“冰河时代”。他说,大约在1996年,他开始认为“日本正在发生的事情将滞后地出现在欧洲和美国”。他解释说,日本股市泡沫的破裂导致了各种糟糕的情况:实际利率崩溃、通胀降至零、债券收益率降至零。最终,日本进入了一段低增长时期,至今未能摆脱。他补充说,与美国的不同之处在于,日本化实际上在2000年互联网泡沫破裂时就开始发生,但随着美联储开始通过量化宽松“撒钱”来解决问题,经济与资产价格之间的“关系破裂了”。他认为,美国从那以后基本上处于一个持续25年的泡沫之中,随时可能破裂——这个“随时”已经说了四分之一个世纪。

“我们最终会在某个时间点面临失控的通胀,”爱德华兹告诉《财富》杂志,“因为,我的意思是,那就是最终结局,对吧?没有人愿意削减赤字。如果这个泡沫破裂,我们重启量化宽松,唯一的解决办法就是更多的量化宽松,然后我们最终陷入通胀,可能比2022年更糟。”

爱德华兹还在房价中看到了确凿证据。“你看看美国房地产市场,你会想,'嗯,实际上,是不是美联储相对于其他地方来说太宽松了?'因为为什么其他房地产泡沫在房价收入比方面已经收缩,而美国却仍然停留在最高估值或接近最高估值的水平?”一番精彩论述展示了为何爱德华兹尽管有“老调重弹”的名声却仍备受尊重,他指出,在2018年彭博观点的一篇文章中,传奇的前美联储主席保罗·沃尔克(Paul Volcker)“在临终前痛斥美联储”。这位在1980年代以遏制通胀著称的央行行长认为,现代宽松的货币政策是“一个严重的判断错误……基本上就是把问题往后推”。爱德华兹向《财富》杂志分享了一张经合组织(OECD)的图表,显示由于美联储过于宽松,美国房地产市场与全球市场脱钩的程度有多大。

这位分析师还表示,他也对私募股权持怀疑态度,他认为这一资产类别从多年来债券收益率下降和杠杆使用中获益匪浅。私募股权的优势在于其税务处理方式以及“它不需要按市价计价,因此波动性不大”。然而,该行业杠杆率很高,他表示,如果全球环境转向债券的长期熊市,那将是一个“重大问题”。近期一些引人注目的破产事件已开始波及债券市场,引发了人们对“信贷蟑螂”的担忧,正如摩根大通(JPMorgan)首席执行官杰米·戴蒙(Jamie Dimon)最近给这个问题贴的标签。

爱德华兹借用“你绝不会只看到一只蟑螂”的比喻警告说,这些破产事件预示着一个高杠杆行业存在更深层次的问题,该行业已将其“触角……深深伸入实体经济”。

《财富》杂志向爱德华兹指出,更多主流、不那么悲观的人士也发出了类似的警告,例如在雅虎财经投资大会上发言的穆罕默德·埃里安(Mohamed El-Erian),以及“债券之王”杰弗里·冈拉克(Jeffrey Gundlach),后者对私募股权同样持怀疑态度。爱德华兹同意空气中弥漫着某种气息。“我想说的是,怀疑的声音更多了。而这又是一件让我担心的事情。这个泡沫可以持续下去。如果它是一个泡沫,它可以持续相当长一段时间。嗯,我们可以把问题一次又一次地往后推。通常情况下,怀疑者会被扫到一边。”

对于那些陷入既害怕崩盘又害怕错过融涨的投资者,爱德华兹建议投资者对他的话持保留态度,但要注意潜在的警告信号。“我说我每年都预测经济衰退,别听我的,但这些是你应该注意的事情。”爱德华兹引用前花旗集团首席执行官查克·普林斯(Chuck Prince)那句用舞会比喻总结泡沫心态的著名言论,建议道:“关于在音乐还在播放时跳舞,你必须决定是站在乐队前面蹦跳,还是在靠近消防通道的地方跳舞,准备第一个离开。”(*)

译者:中慧言-王芳

法国兴业银行(Société Générale)直言不讳的全球策略师阿尔伯特·爱德华兹(Albert Edwards)——他甚至自称“永久熊市论者”——确信,当前主要由高估值科技股和人工智能股驱动的美国股市正深陷危险的泡沫之中。(需要明确的是,法国兴业银行并不认为美股或AI股存在泡沫,并指出爱德华兹的职责是提供内部不同观点。)尽管历史常常重演,但爱德华兹近期警告称,本轮周期崩盘的环境已发生根本性变化,可能导致经济和平民投资者遭受更深远、更痛苦的清算。

“我认为存在泡沫,不过话说回来,我总是认为有泡沫,”爱德华兹最近在彭博社的梅琳·萨默塞特·韦布(Merryn Somerset Webb)的播客节目《Merryn Talks Money》中表示,并指出每个周期总有一个“看似非常合理、极具说服力的叙事”。然而,他的结论坚定不移:“最终会以悲剧收场,这一点我非常肯定。”

爱德华兹在接受《财富》杂志(Fortune)采访时表示,此前关于泡沫的理论“在1999年和2000年初非常令人信服,在2006—2007年也是如此”。他说,每次“市场上涨都如此迅猛”,以至于他不再谈论泡沫,“因为客户会对你重复同样的话却总是说错感到厌烦”,直到泡沫破裂后他们才会改变态度。“通常,当人们被泡沫冲昏头脑时,他们根本不想听,因为他们正在赚大钱。”

正如他本人常指出的那样,爱德华兹以极度看空的市场策略师闻名,他做出过一些引人注目且夸张的预测,经常对股市大幅崩盘和经济衰退发出警告。他的过往记录包括著名的准确预测互联网泡沫,但也包含一些未应验的警告,例如预测标普500指数可能从峰值下跌75%——比2008年金融危机的低点更糟。当《纽约时报》在2010年报道爱德华兹时,他们指出,这位面带微笑、穿着勃肯鞋的分析师自1997年以来就一直预测美国股市将出现日本式的停滞(他在接受《财富》杂志采访时重复了这一预测)。

尽管如此,爱德华兹仍坚持认为,当前情况与1990年代末的纳斯达克泡沫有明显的相似之处:科技股估值极高,一些美国公司的远期市盈率超过30倍,而这都由引人注目的增长叙事所支撑。爱德华兹认为,正如上世纪90年代科技、媒体和电信(TMT)行业吸引了大量(有时是浪费的)资本投资一样,今天的狂热与那个早期时代如出一辙。不过,有两个关键差异可能导致这次的结果要糟糕得多。

缺失的催化剂与融涨风险

爱德华兹解释说,在以前的周期中,泡沫破灭的催化剂通常是货币当局的紧缩周期——即美联储加息,从而暴露市场泡沫。这一次,随着美联储降息,这一催化剂明显缺失。美国银行研究部指出,央行在通胀上升时降息的情况十分罕见,自1973年以来仅占16%。不祥的是,美银在八月份发布了一份关于“2007年幽灵”的报告。

爱德华兹预测,美联储不会收紧政策,反而会因为美国回购市场的问题——这是大衰退时期的另一个幽灵——而停止量化紧缩,并可能“很快”转向量化宽松。美联储本身在2021年就回购问题发布了一份工作人员报告,报告中写道2007年至2009年间的交易“凸显了美国回购市场的重要脆弱性”。回购问题在疫情期间再次出现,里士满联储指出利率从2019年开始“急剧飙升”。

爱德华兹告诉彭博社,缺乏鹰派政策可能导致“进一步融涨”,使得最终的破灭更具破坏性。爱德华兹自嘲道:“我只是厌倦了看空,基本上就像摇着锁链说‘这都是泡沫,全都要崩溃’。”他说,他明白这个泡沫实际上可能持续的时间远超像他这样的永久熊市论者认为合理的时间,“而实际上,正是在那时,会突然冒出一些意外事件,抽走泡沫的根基。”

“人工智能泡沫更令人担忧的是,”爱德华兹告诉《财富》杂志,“经济对这一主题的依赖程度有多深,不仅仅是推动增长的企业投资,”还有消费增长由顶层五分之一人口主导的程度远超平常。换句话说,那些重仓股票的美国最富有人群,对经济的推动作用比以往任何泡沫时期都大,占消费的比例也大得多。“所以,如果你愿意这么说,经济比'87年股灾时更脆弱,”爱德华兹解释道,股市25%或更大幅度的回调意味着消费支出必将受到影响——更不用说50%的暴跌了。

爱德华兹告诉彭博社,他担心被卷入市场、被鼓励“逢低买入”的散户投资者广泛参与。爱德华兹警告说,“股市永远不会下跌”这种信念是危险的,并认为下跌30%甚至50%是完全有可能的。美国社会的不平等以及财富被“股市吹胀”的高收入人群财富高度集中是爱德华兹主要担忧的问题,他指出,如果股市出现重大回调,那么美国的消费将“受到非常、非常严重的打击”,整个经济都将受损。华尔街那些不那么极端看空的人士,如摩根士丹利财富管理的丽莎·沙莱特(Lisa Shalett),也日益认同这一观点。

爱德华兹告诉《财富》杂志,从很多方面看,市场早该回调了,他指出除了疫情期间的两个月,自2008年以来就没有出现过衰退。“这时间真他妈长,而商业周期最终总是会进入衰退的。”他说时间太长了,以至于他作为永久熊市论者的本能都感到困惑。“事实上我现在对即将发生的崩盘不那么担心了,这反而让我担心,”爱德华兹笑着补充道。

爱德华兹告诉《财富》杂志,他经历过各种周期和泡沫,并在1990年代中期确立了他永久熊市论者的地位,当时他感觉到遥远的亚洲正在发生一场地震。“你在这个圈子里混了几次,就会变得愤世嫉俗,”他说,然后又纠正自己:“这个词不对。你会变得对完整的叙事极度怀疑。”他自豪地重复讲述他在90年代在德利佳华(Dresdner Kleinwort)工作时,如何以怀疑的态度撰文评论当时马来西亚的经济繁荣,结果却惊讶地发现泰国先爆发了危机。尽管如此,他说,“因为我的文章,我们失去了(在马来西亚的)所有银行牌照,”并补充说,这个故事仍然自豪地钉在他的X.com账号上。

“我基本上算是得躲在桌子底下,”爱德华兹谈到他内心的熊市观点在公司内部得到的反应时说道。“企业金融银行部门当然不乐意失去所有银行牌照。但回过头看,你知道,他们避免了在马来西亚危机爆发前最后一年向其放贷。他们事后也没谢我。”

财政失控与蟑螂

除[股权估值外,爱德华兹一直强调另外两个指向系统性脆弱性的主要潜在风险。首先,爱德华兹强调了西方由“财政失控”驱动的长期通胀风险。尽管中国带来短期的周期性通缩压力——其GDP平减指数已连续12个季度同比下降——爱德华兹表示,他相信对于负债累累的西方政客来说,阻力最小的路径将是“印钞”。在某个时间点,财政可持续性的计算“根本对不上”,迫使央行通过“收益率曲线控制”或量化宽松进行干预以压低债券收益率。

这就引出了爱德华兹长期持有的关于日本的观点,他称之为“冰河时代”。他说,大约在1996年,他开始认为“日本正在发生的事情将滞后地出现在欧洲和美国”。他解释说,日本股市泡沫的破裂导致了各种糟糕的情况:实际利率崩溃、通胀降至零、债券收益率降至零。最终,日本进入了一段低增长时期,至今未能摆脱。他补充说,与美国的不同之处在于,日本化实际上在2000年互联网泡沫破裂时就开始发生,但随着美联储开始通过量化宽松“撒钱”来解决问题,经济与资产价格之间的“关系破裂了”。他认为,美国从那以后基本上处于一个持续25年的泡沫之中,随时可能破裂——这个“随时”已经说了四分之一个世纪。

“我们最终会在某个时间点面临失控的通胀,”爱德华兹告诉《财富》杂志,“因为,我的意思是,那就是最终结局,对吧?没有人愿意削减赤字。如果这个泡沫破裂,我们重启量化宽松,唯一的解决办法就是更多的量化宽松,然后我们最终陷入通胀,可能比2022年更糟。”

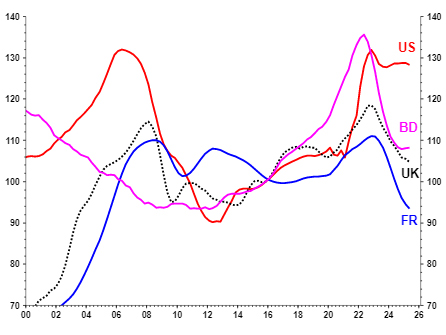

爱德华兹还在房价中看到了确凿证据。“你看看美国房地产市场,你会想,'嗯,实际上,是不是美联储相对于其他地方来说太宽松了?'因为为什么其他房地产泡沫在房价收入比方面已经收缩,而美国却仍然停留在最高估值或接近最高估值的水平?”一番精彩论述展示了为何爱德华兹尽管有“老调重弹”的名声却仍备受尊重,他指出,在2018年彭博观点的一篇文章中,传奇的前美联储主席保罗·沃尔克(Paul Volcker)“在临终前痛斥美联储”。这位在1980年代以遏制通胀著称的央行行长认为,现代宽松的货币政策是“一个严重的判断错误……基本上就是把问题往后推”。爱德华兹向《财富》杂志分享了一张经合组织(OECD)的图表,显示由于美联储过于宽松,美国房地产市场与全球市场脱钩的程度有多大。

这位分析师还表示,他也对私募股权持怀疑态度,他认为这一资产类别从多年来债券收益率下降和杠杆使用中获益匪浅。私募股权的优势在于其税务处理方式以及“它不需要按市价计价,因此波动性不大”。然而,该行业杠杆率很高,他表示,如果全球环境转向债券的长期熊市,那将是一个“重大问题”。近期一些引人注目的破产事件已开始波及债券市场,引发了人们对“信贷蟑螂”的担忧,正如摩根大通(JPMorgan)首席执行官杰米·戴蒙(Jamie Dimon)最近给这个问题贴的标签。

爱德华兹借用“你绝不会只看到一只蟑螂”的比喻警告说,这些破产事件预示着一个高杠杆行业存在更深层次的问题,该行业已将其“触角……深深伸入实体经济”。

《财富》杂志向爱德华兹指出,更多主流、不那么悲观的人士也发出了类似的警告,例如在雅虎财经投资大会上发言的穆罕默德·埃里安(Mohamed El-Erian),以及“债券之王”杰弗里·冈拉克(Jeffrey Gundlach),后者对私募股权同样持怀疑态度。爱德华兹同意空气中弥漫着某种气息。“我想说的是,怀疑的声音更多了。而这又是一件让我担心的事情。这个泡沫可以持续下去。如果它是一个泡沫,它可以持续相当长一段时间。嗯,我们可以把问题一次又一次地往后推。通常情况下,怀疑者会被扫到一边。”

对于那些陷入既害怕崩盘又害怕错过融涨的投资者,爱德华兹建议投资者对他的话持保留态度,但要注意潜在的警告信号。“我说我每年都预测经济衰退,别听我的,但这些是你应该注意的事情。”爱德华兹引用前花旗集团首席执行官查克·普林斯(Chuck Prince)那句用舞会比喻总结泡沫心态的著名言论,建议道:“关于在音乐还在播放时跳舞,你必须决定是站在乐队前面蹦跳,还是在靠近消防通道的地方跳舞,准备第一个离开。”(*)

译者:中慧言-王芳

Albert Edwards, the outspoken Global Strategist at Société Générale---a figure who even refers to himself as a “perma bear”---is certain that the current U.S. equity market, driven largely by high-flying tech and AI, is experiencing a dangerous bubble. (Société Générale, to be clear, does not hold the view that U.S. stocks or AI stocks are in a bubble, noting that Edwards is employed as the in-house alternative view.) While history often repeats itself, Edwards warned recently that the circumstances surrounding this cycle's inevitable collapse are fundamentally different, potentially leading to a deeper and more painful reckoning for the economy and the average investor.

“I think there's a bubble but there again I always think there's a bubble,” Edwards told Bloomberg's Merryn Somerset Webb in a recent appearance on her podcast Merryn Talks Money, noting that during each cycle, there is always a “very plausible narrative, very compelling.” However, he was unwavering in his conclusion: “it will end in tears, that much I'm sure of.”

Edwards told Fortune in an interview that previous theories about a bubble were “very convincing in 1999 and early 2000, they were very convincing in 2006-2007.” Each time, he said, the “surge in the market was so relentless” that he just stopped talking about bubbles, “because clients get pissed off with you repeating the same thing over and over again and being wrong,” only to change their tune after the bubble bursts. “Generally, when you're gripped by a bubble, people just don't want to listen because they're making so much money.”

As he himself frequently points out, Edwards is known as a very bearish market strategist who has made some high-profile and dramatic predictions, often warning about major stock market crashes and recessions. His track record includes famously calling the dot-com bubble, but it also includes warnings that haven't panned out, such as predicting a potential 75% drop in the S&P 500 from peaks---worse than the 2008 financial crisis lows. When The New York Times profiled Edwards in 2010, they noted that the chuckling, birkenstocks-wearing analyst had been predicting a Japan-style stagnation for U.S. equity markets since 1997 (a prediction he repeated in his interview with Fortune).

Still, Edwards insists that the current parallels to the late 1990s NASDAQ bubble are clear: extremely rich valuations in tech, with some U.S. companies trading at over 30x forward earnings, justified by compelling growth narratives. Just as the TMT (Technology, Media, Telecom) sector attracted vast, sometimes wasted, capital investment in the 1990s, Edwards argued that today's enthusiasm echoes that earlier era. There are two key differences that could lead to a much worse outcome this time, though.

The Missing Trigger and the Meltup Risk

In previous cycles, Edwards explained, the catalyst for a bubble's demise was usually the monetary authority's tightening cycle---the Federal Reserve hiking rates and exposing market froth. This time, with the Fed lowering rates, that trigger is conspicuously absent. Bank of America Research has noted the rarity of central banks cutting rates amid rising inflation, which has occurred just 16% of the time since 1973. Ominously, BofA released a note on the “Ghosts of 2007” in August.

Instead of tightening, Edwards anticipates the Fed will move away from quantitative tightening and likely shift to quantitative easing “quite soon,” due to issues in the U.S. repo markets, another ghost from the Great Recession. The Fed itself issued a staff report in 2021 on repo issues, writing in 2021 that trading between 2007 and 2009 “highlighted important vulnerabilities of the US repo market.” Repo issues reemerged in the pandemic, with the Richmond Fed noting that interest rates “spiked dramatically higher” starting in 2019.

Edwards told Bloomberg that the absence of hawkish policy could lead to a “further meltup,” making the eventual burst even more damaging. Poking fun at himself, Edwards said, “I just got bored being bearish, basically rattling my chains saying, 'This is all a bubble, it's all going to collapse.'” He said that he can see how the bubble can actually keep going for much longer than a perma bear like himself would find logical, “and actually that's when something just comes out the woodwork and takes the legs from out from under the bubble.”

“What's more worrying about the AI bubble,” Edwards told Fortune, “is how much more dependent the economy is on this theme, not just for the business investments, which is driving growth,” but also the fact that consumption growth is being dominated far more than normal by the top quintile. In other words, the richest Americans who are heavily invested in equities, are driving more of the economy than during previous bubbles, accounting for a much larger proportion of consumption. “So the economy, if you like, is more vulnerable than it was in the '87 crash,” Edwards explained, with a 25% or greater correction in stocks meaning that consumer spending will surely suffer---let alone a 50% lurch.

Edwards told Bloomberg he was concerned about the widespread participation of retail investors who have been dragged into the market, encouraged to “just buy the dips.” This belief that “the stock market never goes down” is dangerous, Edwards warned, arguing that a 30% or even a 50% decline is very possible. The inequality of American society and the heavy concentration among high earners whose wealth has been “inflated by the stock market” is a major concern for Edwards, who pointed out that if there is a major stock-market correction, then U.S. consumption will be “hit very, very badly indeed” and the entire economy will suffer. This view is increasingly shared by less uber-bearish voices on Wall Street, such as Morgan Stanley Wealth Management's Lisa Shalett.

In many ways, Edwards told Fortune, we're overdue for a correction, noting that apart from two months during the pandemic, there hasn't been a recession since 2008. “That's a bloody long time, and the business cycle eventually always goes into recession.” He said it's been so long that his perma-bear instincts are confused. “The fact I'm less worried about an imminent collapse [right now] makes me worried,” Edwards added with a laugh.

Edwards told Fortune that he's been through various cycles and bubbles and he gained his perma-bear status in the mid-1990s, when he felt a distant earthquake happening in Asia. “You've been around the block a few times, you just do become cynical,” he said, before correcting himself: “That's not the right word. You become extremely skeptical of the full narrative.” He proudly repeats the story about how, when he was at Dresdner Kleinwort in the '90s, he wrote with skepticism about Malaysia's economic boom at the time, only to be surprised when Thailand blew up first. Nevertheless, he said, “we lost all our banking licenses [in Malaysia] because of what I wrote,” adding that the story is still proudly pinned to his X.com account.

“I had to sort of basically hide under my desk,” Edwards said of the inward reception to the emergence of his inner bear. “Corporate finance banking departments certainly didn't appreciate losing all their banking licenses. But in retrospect, you know, they avoided a final year of lending to Malaysia before it blew up. They didn't thank me afterwards.”

Fiscal Incontinence and Cockroaches

Beyond equity valuations, Edwards has been highlighting two other major underlying risks point to systemic vulnerability. First, Edwards highlighted the long-term risk of inflation in the West, driven by “fiscal incontinence.” Despite short-term cyclical deflationary pressure emanating from China---which has seen 12 successive quarters of year-on-year declines in its GDP deflator---Edwards said he believes the path of least resistance for highly indebted Western politicians will be “money printing.” At some point, the mathematics for fiscal sustainability “just do not add up,” forcing central banks to intervene through “yield curve control” or quantitative easing to hold down bond yields.

This is where Edwards' long-held thesis about Japan comes in, what he calls “The Ice Age.” Around 1996, he said, he started thinking that “what's happening in Japan will come to Europe and the U.S. with a lag.” He explained that the bursting of the Japanese stock bubble led to all kinds of nasty things: real interest rates collapsing, inflation going to zero, bond yields going to zero. Ultimately, it was a period of low growth that Japan still has not been able to break out of. The difference with the U.S., he added, is that Japanification actually started happening in 2000 with the dot-com bubble bursting, but “the relationship broke” between the economy and asset prices as the Fed began “throwing money” at the problem through QE. The U.S. has essentially been in a 25-year bubble since then that is due to burst any day now, he argued---it's been due any day for a quarter-century.

“We're going to end up with runaway inflation at some point,” Edwards told Fortune, “because, I mean, that's the end game, right? There's no appetite to cut back the deficits. We bring back the QE, if and when this bubble bursts, the only solution is more QE, and then we end up with inflation, maybe even worse than 2022.”

Edwards also sees a smoking gun in home prices. “You look at the U.S. housing market, you think, 'Well, actually, is the Fed just too loose relative to everywhere else?' Because why should other housing bubbles have deflated in terms of house price earnings ratio, but the U.S. is still stuck up there at maximum valuation or close to it?” In a flourish that shows why Edwards is so respected despite his broken-record reputation, he notes that in a Bloomberg Opinion piece from 2018, legendary former Fed chair Paul Volcker “eviscerated the Fed just before he died.” The central banker who famously slew inflation in the 1980s argued that the modern era's loose monetary policy was “a grave error of judgment ... basically just kicking the can down the road.” Edwards shared an OECD chart with Fortune to show just how much U.S. housing has decoupled from global markets because the Fed has been too loose.

The analyst also said he applied his skepticism to private equity, an asset class that he sees having benefited immensely from years of falling bond yields and leverage. Private equity's advantage has been its tax treatment and the fact that “it doesn't have to mark itself to market, so it isn't very volatile.” However, the sector is highly leveraged, and if the global environment shifts to a secular bear market for bonds, he said that would be a “major problem.” Recent high-profile bankruptcies have started to leak into bond markets, prompting concern of “credit cockroaches,” as JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon recently labeled the issue.

Drawing on the metaphor that “you never have just one cockroach,” Edwards warned that these bankruptcies signal deeper issues in a highly leveraged sector that has spread its “tentacles... deeply into the real economy.”

Fortune notes to Edwards that more mainstream, less bearish voices are sounding similar warnings, Mohamed El-Erian at the Yahoo Finance Invest conference and Jeffrey Gundlach, the “bond king,” who takes a similarly skeptical view of private equity. Edwards agreed that something is in the air. “I would say there are more voices of skepticism. And again, this is one thing which makes me worry. This bubble can go on. If it is a bubble can go on quite a long while. Well, we can kick the can down the road many times. Normally, the skeptics are swept aside.”

For investors trapped between the fear of a collapse and the fear of missing a meltup, Edwards told advised investors to take him with a grain of salt but be mindful of potential warning sings. “I say that I predict a recession every year, don't listen to me, but these are the things you should be looking out for.” Paraphrasing an infamous quote from former Citi CEO Chuck Prince that summed up the bubble mentality with a metaphor about a dance party, Edwards recommended: “In terms of dancing while the music's still playing, you have to decide whether to be in front of the band, pogoing, or dancing close to the fire escape, ready to get out first.”